Rome Underground

Rediscovering the Catacombs in the 17th Century

The catacombs of Rome form ‘a subterranean city of the dead’ and over the years captured the imagination of many. One of the scholars to visit the catacombs was Antonio Bosio. He was so overwhelmed by the greatness of this labyrinthine construction that he was afraid to die there. What was his reason to keep entering these catacombs in spite of his fear and to write his magnum opus on them?

Historical development of the catacombs

The catacombs of Rome were located outside the city walls and came into use in the second century A.D. by pagans, Christians and Jews. They date mostly from the period until 313 A.D., the year in which Constantine established what George Edmundson calls ‘the peace of the Church’ in the Roman Empire, after which prosecution did not threaten the Christians anymore. From that year on people wanted to be buried near the martyrs, who had been buried here before. This was the start of the so-called ‘cult of the martyrs’, which from the fourth century A.D. onwards attracted many pilgrims to the catacombs, using Itineraries (guide books) to visit the tombs of martyrs and pray. During this period the extensively decorated catacombs in combination with eyecatching monuments above ground were constructed. The early burials namely were simple, mostly without decorations and more or less similar to each other. The catacombs were used for actual burials until the fifth century, during which people were buried above the surface or in basilicas by order of the Church. From the seventh century onwards robbers started invading the catacombs. Therefore, the remains of some of the martyrs were being taken away precautionally and brought to churches inside the city of Rome. This process reached its climax in the period between 817 and 824 A.D. As a result, pilgrims came to the catacombs less and less and the catacombs were gradually forgotten.

Rediscovering the Roman catacombs

The catacombs were being explored again in the end of the 15th century. Interest into the catacombs definitively came back into existence after the accidental discovery of the catacombs at the Via Salaria in 1578. During the Counter-Reformation there was much interest in the catacombs in order to search for evidence of early Christian life in Rome. Starting on 10 December 1593, extensive research on the Roman catacombs was executed by the Italian archaeologist Antonio Bosio (c. 1575-1629). This research had both an intellectual and religious background, which was supplied by the Roman Oratory. Because of his (scientific) approach, Bosio can be seen, as Edmundson states, as the ‘real founder of Christian archaeology’. The publication of the editio princeps of his work Roma Sotterranea started after his dead in 1632 and was edited by Giovanni Severani. In this work, Bosio describes the catacombs that were accessible for him and provides illustrations of the paintings and objects found in the catacombs. According to Leonard Rutgers, he was ‘an authority on everything related to underground Rome’, and Roma Sotterranea became ‘the standard reference work on catacombs'.

|

| Close-up of an illustration of a painting found in a catacomb at the Via Salaria from Bosio's Roma Sotterranea (1650). |

|

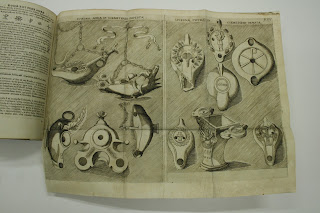

| Illustration of oil lamps found in the catacombs at the Via Latina from Bosio's Roma Sotterranea (1650). |

|

| Title page of Bosio's Roma Sotterranea (1650). |

The edition present in the KNIR library was published in 1650 in Rome for Lodovico Grignani on the occasion of the Holy Year. It contains the same text as the editio princeps, but a smaller amount of images in order to reduce the size and keep the book user friendly (or as stated in the preface ‘la più commoda forma che mai sia stata’; the most comfortable format there is). Therefore, this particular book is called Bosietto, meaning ‘Little Bosio’. One can imagine that, since this book was cheaper than the editio princeps which was a big folio format with a lot of illustrations, it reached a much wider audience that could use it as a guide book for the catacombs while visiting Rome during the Holy Year.

|

| General map of Rome, which is included at the beginning of book 2 of Bosio's Roma Sotterranea (1650). |

|

| Maps of the catacombs of San Callisto from Bosio's Roma Sotterranea (1650). |

Afterlife of Bosio’s Roma Sotterranea

Bosio’s work is of very high importance since many catacombs were being destroyed and plundered in the two centuries afterwards, during which the search for relics of saints was the most important goal of explorers of the catacombs. Therefore, Roma Sotterranea contains much information that is lost now.

It was translated into Latin by a cleric at the Roman Oratory, called Paolo Aringhi (1600-1676). His work Roma subterranea novissima was first published in 1651 and reached a much wider audience throughout Europe because of its language. This work, however, was not a literal translation, but as stated by Rutgers ‘a free rendering into which Aringhi inserted many observations of his own’. This work has a stronger Counter-Reformation based accent. Besides, Aringhi is expressing what Rutgers calls ‘anti-Judaic sentiments’ throughout his work, which (indirectly) influences the thought of the readers. Since many scholars were reached by the Latin translation who were not able to read the Italian work of Bosio, they did not notice this. This is important to realise when consulting Aringhi’s work.

Aringhi was definitely not the last one to be struck by the catacombs and many scholars and non-scholars are still intrigued by the secrets of the subterranean world of Rome thanks to Antonio Bosio and his marvellous work. E. Boschma

BOSIO

Antonio Bosio [Roma Sotterranea] Roma Sotterranea Opera Postuma di Antonio Bosio Romano Antiquario Ecclisiastico singolare de’suoi tempi. [...] Compita, Disposta, & Accresciuta dal P. Giovanni Severani da S. Severino, Sacerdote della Congregatione dell’Oratorio di Roma. (In ROMA, per Lodovico Grignani l’Anno Santo M. DC. L. Con Licenza de’Superiori.)

4°, 12 - 704 - 29.

Rome, Library Koninklijk Nederlands Instituut Rome DR90

Bibliography

“Antonio Bosio, Roma Sotterranea.” The Theater That Was Rome. Brown University. 2015. 29

November 2015. <https://library.brown.edu/projects/rome/essays/bosio_essay/>

“Bosio, Antonio.” Dizionario Biografico Degli Italiani. Vol. 13. 1971.

Ditchfeld, Simon. “Ancient.” Rev. of Roma Sotterranea, by Antonio Bosio. The Catholic Historical

Review April 2000: 305-308. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/25025720>

Edmundson, George. The Church in Rome in the First Century: An Examination of Various

Controverted Questions Related to its History, Chronology, Literature and Traditions. Eugene:

Wipf and Stock, 2008.

Erenstoft, Jamie Beth. Controlling the Sacred Past: Rome, Pius IX, and Christian Archaeology. Diss.

State University of New York at Buffalo, 2008. Ann Arbor: UMI, 2008. 3320468.

Johnson, Allan Chester, Paul Robinson Coleman-Norton and Frank Card Bourne. Ancient Roman

Statutes: A Translation with Introduction, Commentary, Glossary, and Index. Ed. Clyde Pharr.

Clark: Lawbook Exchange, 2003.

Lewis, Nicola Denzey. “Reinterpreting ‘Pagans’ and ‘Christians’ from Rome’s Late Antique

Mortuary Evidence.” Pagans and Christians in Late Antique Rome. Ed. Michele Salzman,

Marianne Sághy and Rita Lizzi Testa. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2015. 273-290.

Livingstone, Elizabeth, ed. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. 3rd ed. Oxford:

Oxford UP, published online: 2014. Current online version: 2015. Web. 20 November 2015.

<http://www.oxfordreference.com>

“Origins of Catacombs.” The Christian Catacombs of Rome. Istituto Salesiano San Callisto - Rome.

N.d. 29 November 2015. <http://www.catacombe.roma.it/en/origini.php>

Pergola, Philippe. Christian Rome: Early Christian Rome: Catacombs and Basilicas. Rome: Getty Publications, 2000.

Rutgers, Leonard V. The Jews in Late Ancient Rome: Evidence of Cultural Interaction in the

Roman Diaspora. Leiden: Brill, 2000.

Stevenson, James. The Catacombs: Rediscoverd Monuments of Early Christianity. London: Thames and Hudson, 1978.

0 comments